Episode 15 – The Dunblane Massacre

Many of us have heard about the horrible mass shooting that occurred on May 24 in Uvalde, Texas, United States and left 19 students and two teachers dead. What makes the situation even more tragic is the fact that this year alone, within just six months, there have been 27 school shootings in the US. If we put together all incidents from the last four years, the number is 119—one hundred and nineteen. Of course, the US is not the only place where shootings happen. In the United Kingdom, the last school shooting was almost as deadly as the one in Texas—it just took place nearly three decades ago.

In Dunblane Primary School in Stirling, the school day on March 13, 1996, had started like any other morning at 9 AM for its 640 pupils. Morning assemblies were held in the school’s Assembly Hall, next to the dining area and the gymnasium, on a rotating schedule due to the limited size of the hall. Afterwards, the year groups dispersed to their respective classrooms—except for Primary 1/13, who, with teacher Gwen Mayor, had made their way to the gymnasium. A supervisory assistant, Mary Blake and physical education teacher, Eileen Harrild, were then supposed to relieve Gwen to enable her to attend a meeting. Before doing so, Eileen exchanged a few words with Gwen—but their conversation was interrupted by sudden and terribly loud noises. As the two women turned around, they saw a man entering the gym wearing a dark jacket, black corduroy trousers and a wooly hat with ear defenders. The teachers and the children barely had any time to realise what was happening or see the pistol in the man’s hand before he raised the weapon and fired indiscriminately and in rapid succession. Eileen was hit in both forearms, the right hand and the left breast, but she was able to stumble into the open-plan store area together with Mary and a number of children. Gwen, however, was killed instantly, in addition to one of the students.

For more horrifying true crime stories, please click below:

Archives

The shooter continued walking around the gym, firing altogether over 50 bullets—some at point-blank range at children who had been thrown to the floor. The man then advanced to the south end of the gym, again firing randomly in every direction and through a window, possibly aiming at an adult who was walking across the playground before opening the fire escape door and stepping outside the doorway. Next, the shooter fired four shots toward the library cloakroom, striking a staff member, Mrs Grace Tweddle, on the head. Finally, the killer discharged nine bullets into a mobile classroom where Catherine Gordon had just instructed her Primary 7 class to get down onto the floor—most of the shots embedded in books and equipment, one passing through a chair on which a child had been sitting second before.

The shooter then returned to the gym—there, he drew a revolver, placed the barrel in his mouth and pulled the trigger. The whole shooting lasted for only 3-4 minutes, but the results were devastating. Gwen Mayor and 15 children lay dead in the gym, and one further child was critically injured. The victims sustained a total of 58 gunshot wounds, of which 26 were fatal. Only one of the child victims survived long enough to be taken to the hospital but, in the end, had been pronounced dead on arrival. Fifteen others were injured.

The first call to authorities was made at 9:41 AM by the school’s headmaster Ronald Taylor who had been alerted of the possibility of a gunman on the school premises. Assistant headmistress Agnes Awlson had not yet seen what had happened, but she had heard the screams and noticed what she thought to be cartridges on the ground. After the first call, Ronald ran along the corridor to the gym—on the way, he was told by a teacher he had seen the gunman shooting himself. Ronald burst into the gym and was met with what he described as “a scene of unimaginable carnage, one’s worst nightmare.” Some of the children were crying, and some of them were completely motionless. After asking the teacher to comfort the students, Ronald returned to his office and told deputy headmistress Fiona Eadington to call for ambulances, a call which was made at 9:43 AM. The first ambulance arrived at Dunblane Primary School at 9:57 AM— Medical teams from the health centres in Doune and Callander followed shortly after. In addition, over 100 police officers were at the scene that day. By about 11:10 AM, all of the injured had been taken to Stirling Royal Infirmary.

What was left was the heartbreaking task of the families of the slaughtered children to formally identify them and begin their grieving process, trying to understand how someone could have taken their loved one from them in such a brutal way.

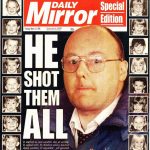

That someone, the shooter, was soon identified as 43-year-old Thomas Hamilton. As Thomas was not available to answer any questions and explain what had driven him to kill 17 people and himself, the authorities dug deeply into his background and character, trying to piece together a possible motive.

We will start with Thomas’ mother, Agnes Hamilton, who was born in 1931 as an illegitimate daughter of a widowed mother. Having a child in such circumstances could have caused a scandal back then, and so, baby Agnes was given away to relatives, James and Catherine Hamilton, who raised the girl as their own. When Agnes was 19, she met a bus driver named Thomas Watt and fell in love. The couple got married soon after in Bridge Church, Glasgow, in 1950 and a couple of years later, on May 10, 1952, they had a son—who was also named Thomas.

Unfortunately, Agnes and her husband’s marriage did not last, and Thomas Sr. ran off with another woman soon after their son’s birth. Afterwards, Agnes returned to her adoptive parents, who helped to conceal another potential scandal—James and Catherine adopted Thomas and Agnes became his older sister. For half of his life, Thomas believed his biological mother was actually his sister.

After primary education in Cranhill and Stirling, Thomas attended Riverside Secondary School and eventually Falkirk Technical College, being a relatively bright student. After his graduation in 1968, Thomas became an apprentice draughtsman in the County Architect’s Office in Stirling and eventually opened his own shop in 1972 at 49 Cowane Street, known as “Woodcraft.” Thomas specialised in things like ironmongery and selling DIY goods and supplies in addition to fitted kitchens.

Woodcraft remained open for over a decade, indicating Thomas was definitely doing something right. But during those years, he was also accused of strange behaviour. At the age of 20, Thomas had become an assistant Boy Scout leader of the 4th/6th Stirling Troop. He appeared very keen and willing and did not present any problems during regular checkups. Thomas did, however, once try to take some boys on his boat on Loch Lomond for their proficiency badge work even though his boat had insufficient lifejackets and Thomas himself had inadequate knowledge of the waters. Nevertheless, in the autumn of 1973, Thomas was seconded to be the leader of the 24th Stirlingshire troop, which was being revived. Shortly after, several complaints about Thomas’ leadership followed.

These complaints included Thomas forcing boys to sleep overnight in his company in a van during hill-walking expeditions in freezing weather at Aviemore. The first time something like this happened, Thomas claimed they were supposed to spend a night in a room he had booked, but there had been a double-booking issue. But when the same thing happened again, it was discovered that no bookings had ever been made by Thomas Hamilton. Following the revelation, The County Commissioner, Brian D Fairgrieve and the District Commissioner, R.C.H Deuchars, agreed it would be best for Thomas to resign.

Commissioner Fairgrieve was the one speaking with Thomas after the decision, and he later said that Thomas did not seem like a particularly stable person. Fairgrieve said:

“I formed the impression that he had a persecution complex, that he had delusions of grandeur and I felt his actions were almost paranoia.”

Thomas was then informed that his warrant was being withdrawn due to his lack of leadership qualities. To put it mildly, Thomas was not happy with the decision. When Commissioner Deuchars wrote to him asking Thomas to return his warrant book, he failed to do so for some months. In Thomas’ head, he had done nothing wrong and he was willing to fight to keep his position.

Meanwhile, Commissioner Fairfrive wrote the following letter dated June 29, 1974 to the Scottish Scout Headquarters to explain why Thomas Hamilton should not be a member of the Scout movement any longer:

“While unable to give concrete evidence against this man I feel that too many ‘incidents’ relate to him such that I am far from happy about his having any association with Scouts. He has displayed irresponsible acts on outdoor activities by taking young ‘favourite’ Scouts for weekends during the winter and sleeping in his van, the excuse for these outings being hillwalking expeditions. The lack of precautions for such outdoor activities displays either irresponsibility or an ulterior motive for sleeping with the boys…… His personality displays evidence of a persecution complex coupled with rather grandiose delusions of his own abilities. As a doctor, and with my clinical acumen only, I am suspicious of his moral intentions towards boys”.

Commissioner Deauchars also informed the Scout Headquarters about Thomas’ immaturity and irresponsibility, resulting in him being entered on the “blacklist.” It was later found out that Thomas had written a letter dated April 28, 1974, to Commissioner Deauchars in which he resigned as Scout leader of the 24th Stirlingshire troop. The only thing is that Deauchars said he had never seen such a letter, and there was no record of it on the Scout files—the only logical explanation was that Thomas wrote the letter after he was told about the withdrawal of his warrant. He had simply added the wrong date to create a false impression that he had made the decision to resign.

By 1977, Thomas had made several attempts to return to scouting, including an attempt to become a Scout leader in Clackmannanshire—which failed due to his name being on the blacklist. Thomas then requested the Scout Association to hold a Committee of Inquiry into his complaint that he had been victimised, but the request was denied. Thomas still kept complaining, sending letters here and there and offering his services as a Scout Leader to other Commissioners, but nothing worked. Thomas felt that the Scouts had ruined his reputation, but that did not stop him from setting up and running boys’ clubs.

It is not clear when exactly Thomas began running these clubs, but in the late 1970s, he led one called “Dunblane Rovers” in the Duckburn Centre in Dunblane. He also ran a Rovers Group in Bannockburn. Altogether, from 1981 until 1996, Thomas organised and operated 15 boys’ clubs for various periods on school premises in Central, Lothian, Fife and Strathclyde Regions. Thomas was very active in seeking for children to participate. He would send leaflets to houses and primary schools in the area aiming to reach boys between ages 7 and 11.

The club activities included such things as different games and sports, including football and gymnastics. The boys were charged 30p to £1.50 per attendance, and at first, the clubs were extremely popular, making Thomas a modest income. But as time passed; the numbers dropped drastically, typically to less than a dozen boys. Thomas explained this by children’s lack of patience and determination—but the real reason for decreasing the number of participants was Thomas himself.

Thomas claimed he had noble purposes for running the clubs, like keeping the boys off the streets and helping them stay in shape. However, witnesses described Thomas as almost overly domineering, creating a nearly military-like environment.

Some of the adults who saw Thomas with the boys felt like he was getting something from dominating the children, and it made the witnesses very uneasy. On top of that, Thomas seemed to be oddly interested in individual boys—he clearly had favourites. Sometimes Thomas even pressured the boys who had been at his clubs once to pressure their parents to permit them to attend one of his summer camps. The parents of the children also found it weird how eager Thomas was to pick their boys up from home and try to learn private things from their family background. One thing that particularly made some adults’ hair stand up on the back of their neck was the black, ill-fitting swimming trunks Thomas demanded the boys to use for gymnastics and his habit of taking pictures of the children while they wore those specific trunks. Thomas never asked for permission from the boys’ parents to film them, but as soon as someone found out what he was doing, he explained it was totally normal to take photographs for training and advertising purposes and said that parents could obtain copies from him. While there was no evidence of Thomas doing something terrible to these children, it was noted that the boys did not really seem to enjoy their time at the clubs, and Thomas himself gave a weird feeling to every parent or other adult he met.

If parents then felt too uncomfortable and withdrew their child from the club, Thomas would send them long and repeated letters saying the rumours of him were not true. Some of these letters Thomas hand-delivered—during nighttime. It is not really surprising Thomas Hamilton eventually became known as Mr Creepy, and several complaints were filed against him by the parents.

Later, after the events in Dunblane Primary School had taken place, the Inquiry heard about two incidents during which Thomas had acted inappropriately toward the young boys. Firstly, a 12-year-old boy who had attended Dunblane Rovers at the Duckburn Centre in 1979 or 1980 said he had sat next to Thomas when he suddenly began to rub inside of his leg. According to the witness’s later testimony, Thomas had then asked him why he wanted to be one of his boys and join the club. The boy eventually told about the incident to his father but went back to the club the following week—Thomas just refused to let the boy in because “he was not mature enough.”

The second incident was way more severe in nature, but in the Public Inquiry into the shooting, it was noted this particular witness was unwilling to be identified, only provided their statement in written form and had been convicted of a serious crime of dishonesty in the past. There was also no other evidence to support this person’s claims, which included Thomas Hamilton touching the 12-year-old’s private parts inside the cabin of his boat with his erect penis out of his pants. There may be some truth in this statement, but the police were unable to confirm it. But whether or not this particular incident actually happened or not, the results were the same. Rumours of Thomas Hamilton’s disturbing behaviour circulated, and fewer and fewer boys attended his clubs. Still, Thomas felt hesitant to stop the clubs altogether—he thought he would just make the people believe the rumours of him were true by doing so.

Still, in September 1995, Thomas had to face reality—three clubs had already ended earlier that year, and now just one boy attended the Callander club. Most of his operation was dying, even though five boys from Dunblane still participated at the Dunblane Boys Club. Thomas had to come up with something else, and so he applied for the use of Dunblane High School for a summer training course in 1996. In addition, even though the boys’ clubs had required Thomas’ full attention until this point and he had not been active with his other hobbies, he now began to find his interest in firearms again. Records showed that Thomas’ had not bought ammunition from October 22, 1987, until September 1995. But from that point forward, he was actively shooting again and purchased a total of 1700 rounds of 9 mm and 500 rounds of .357 ammunition between September 22, 1995, and February 27 1996. Thomas also purchased a 9 mm Browning pistol and a .357 Smith & Wesson revolver.

Thomas’ newfound interest in firearms did not go unnoticed. He was often seen at the Whitestone range used by the Stirling Rifle and Pistol Club. The president of the club, Mr G.F. Smith, noted Thomas was a reasonably good shooter—even though he found it a little weird, he fired all the time very rapidly. Thomas’ cousin, Alexis Fawcett, later recalled how beloved the firearms had been for him, saying: “He talks about guns as though they were babies.”

So, something had begun to change in Thomas Hamilton. The Inquiry into the shooting pieced together the last six months before the massacre of Dunblane Primary School to see what was going on inside Thomas’ head during that time. Firstly, Thomas felt like the rumours about him were the reason why he eventually lost his “Woodcraft” shop, not seeing anything wrong in his own behaviour. He was also, desperately trying to recruit boys into his clubs—often lying about the activities, his own qualifications, the number of helpers and the charges. Thomas then abused parents who withdrew their sons—he appeared extremely intolerant of those who questioned the way he ran the clubs and camps. In addition, Thomas had never let go of his grievance against the Scouts and the police—the police because they, according to Thomas, were biased in favour of the “brotherhood of masons.” One thing that the investigators discovered was the fact that Thomas Hamilton did not form any close relationship with an adult of either sex during his lifetime. Agnes, however, did say her son had one girlfriend, but it was a very long time ago.

According to Mr F.B Cullen, who assisted Thomas in his shop, he was always nervous among adults and very uncomfortable amongst women in particular. While there was no concrete evidence suggesting Thomas was interested in young boys in a sexual way, some of his actions did point in that direction. When there was then a substantial decline in his clubs in 1995, Thomas likely started to feel like the most important thing, the purpose in his life, was taken away. It says a lot that around this time, Thomas issued a large number of letters to parents in Dunblane in order to deal with the false and misleading gossip about him—he was desperate.

As Thomas then applied for the use of Dunblane High School for a summer training course in 1996, it indicated he was still very much actively continuing his club activities. At the same time, Thomas became much more active as a shooter—Mr. J.O Gillespie, who was a reasonably frequent visitor to the Hamilton residence, later told the authorities about one incident in February 1996. According to him, Thomas had his 9mm pistol in his hand that day when he asked if Gillespie had any children he would allow to attend his club. When Gillespie said no, Thomas pointed the pistol at him and pulled the trigger—nothing was in the chamber, but Gillespie’s heart likely stopped for a moment. He did not report the incident to the police as he was sure Thomas would just deny everything, and nothing would come of it. But from that moment, Gillespie stopped visiting and felt that Thomas Hamilton was actually a dangerous man. Apparently, one gun club had also refused to let Thomas join due to two members who knew him saying the club should have nothing to do with him.

Then, on March 1, 1996, a parent of an 11-year-old boy filed a complaint against Thomas, saying he appeared to be taking an exceptional interest in her son and one of his friends and had shown the boys a gun before offering to take the boys shooting. There was supposed to be a social worker visit, but the events less than two weeks later intervened before any further steps could be taken.

One more thing that the investigators noted was Thomas’ poor situation with money. He basically had nothing but debt, and his application for a further loan in 1996 had been refused. Some witnesses later stated Thomas had appeared very subdued and depressed by the end of February. Thomas had said to a photographer Mr R.P.C Allston that he was shooting more and more because it took his mind off his problems. On the evening of March 12, Thomas spoke with Mr D. Macdonald on the phone, saying he was lonely, and it was not good to be alone.

The following morning, at about 8:15 AM on March 13, 1996, Thomas Hamilton was seen by a neighbour scraping ice off a white van outside his home at 7 Kent Road, Stirling. The two had a conversation without anything seeming out of the ordinary. Sometime later, Thomas got in his van and drove off in the direction of Dunblane. He parked beside a telegraph pole in the lower car park of Dunblane Primary School at about 9:30 AM. Until this point, there had not been anything strange in Thomas Hamilton’s behaviour—it had been almost like any other Wednesday morning. But what Thomas did now was far from ordinary. He took out a pair of pliers and cut the telephone wires at the foot of the telegraph pole. This did not affect the school but a number of adjoining houses.

Thomas then made his way across the car park towards the school building carrying 743 cartridges of ammunition, two 9mm Browning HP pistols and two Smith & Wesson M19 .357 Magnum revolvers before getting inside through the northwest side door—avoiding the people near the main entrance at the time. Altogether, the school had six entrances and two doors controlled by push bars for emergency exits. The one Thomas used was the closest entrance to the gym where the children were just about to start their P.E class.

Nobody but Thomas Hamilton himself knows why he entered Dunblane Primary School that day and killed over a dozen young, innocent children. But even not knowing the true motives behind the massacre, the people of Dunblane knew something had to be done so a similar nightmare could never occur again. The Cullen Inquiry into the massacre recommended changes in school security and that the government introduce tighter controls on handgun ownership. Even an outright ban on private ownership was put on the table, but The Home Affairs Select Committee stated that a handgun ban would not be appropriate.

Some of the parents of the victims at Dunblane and the Hungerford Massacre supported a group called Gun Control Network that was founded after the shooting. Campaigns to ban private gun ownership quickly gained 705,000 signatures—eventually, in response to the public debate, the then-current Conservative government of John Major introduced the Firearms (Amendment) Act This meant a ban for all cartridge ammunition handguns except .22 calibre single-shot weapons in England, Scotland and Wales. The .22 calibre handguns were also soon banned by the Labour government of Prime Minister Tony Blair, who introduced the Firearms (Amendment) (No. 2) Act 1997. And what was the result? Since the day Thomas Hamilton walked into Dunblane Primary School and slaughtered 16 children and one teacher, there has not been a single school shooting in the United Kingdom. The argument often made by the gun lobby in the United States says that banning guns is not the answer because then they should ban things like cricket bats, too, because both can be dangerous when misused. And yet, in many countries, gun bans have stopped school shootings and even mass shootings altogether, and nobody has ever committed mass murder with a cricket bat.

Episode Credits:

Host – Rhiannon Doe

Voiceover – Kwesi

Website layout & design – Fran Howard

NEWS ARTICLES & RESOURCES

The Public Inquiry into the Shootings at Dunblane Primary School on 13 March 1996

Thomas Watt HAMILTON

Thomas Hamilton

Mass shootings and gun control

The life and death of Thomas Watt Hamilton

In Britain, it took just one school shooting to pass major gun control

Are you going to ban cricket bats?

Explained | The 1996 Dunblane massacre that led to stricter gun laws in the U.K.

Andy Murray says survivor’s account of Uvalde, Texas shooting similar to his experience in 1996 Dunblane massacre

Britain’s deadliest mass shooting changed gun laws forever. But it took a battle to get there.

My daughter was killed at Dunblane. I know that gun controls save lives